From The Genesis until the end of the Second World War

The Genesis

The idea of the foundation of the Hungarian Military History Museum was conceived after the Austro–Hungarian Compromise of 1867 and the subject kept re-surfacing as a political issue. The Austro–Hungarian Monarchy had its own military history museum in Vienna, and most Hungarian relics were then transferred to the Imperial and Royal public collection in Vienna.

The initiative to establish an independent Hungarian military museum was by proposal of the Military Science Committee of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The proposal was submitted to the Minister of Religion and Public Education in December 1888. The committee proposed a gradual expansion of the military historical collection of the Hungarian National Museum and its building. The Hungarian Diet also put this issue on its agenda, and, by resolution, it also supported the foundation of a distinguished Hungarian military historical collection. The Millennium of the Hungarian Conquest in 1896 considerably accelerated preparations. The military historical committee of the Millennium exhibition turned to the competent authorities at the outset and requested them to keep together the military historical collection that was going to be meticulously documented and registered on a national level for the exhibition.

Having been encouraged by the success of the Millennium exhibition, the then Minister of Religion and Public Education not only guaranteed his support for the Hungarian military museum to be set up, but also proposed the military historical collection of the Hungarian National Museum be transferred to it. However these promises came to nothing for various reasons and part of the collection ended up being transferred to Vienna and other parts simply disappeared.

The Great War created a new situation. The only place available to store the large variety of war relics consciously collected from the beginning, as well as the enormous amount of war booty, was the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum in Vienna. To solve the pressing issue of storage space which had come about by 1916 the common Minister of Military Affairs formulated a scheme to construct a new and suitably sized museum block in Vienna. However, he did not rule out the safeguarding of the overspill at “affiliate military museums.” Baron Sándor Szurmay, the Hungarian Minister of Defence took advantage of this situation in order to promote the foundation of an independent military museum in Budapest. The core team of this enterprise was the sub-branch responsible for museological collection of the Ministry’s archives division that had existed since November 1915. The museum was planned to include the military archives as well. Following protracted political skirmishing, Emperor Charles I of Austria (King Charles IV of Hungary) gave his preliminary consent to this plan being submitted to the Council of Ministers. The latter approved this concept and also consented to the construction of the museum to be built on a plot on Gellért Hill in Budapest to be provided by the capital free of charge.

The Museum’s History between 1918 and 1945

However, it was not possible in the final days of the Great War to bring this plan to fruition, nor in the revolutionary atmosphere which followed the collapse of the Monarchy.

Nevertheless, due to their own efforts in the middle of November 1918 Lieutenant Colonel (later General) János Gabányi and Captain (later Colonel) Kamil Aggházy, both of Division 1/a of the Ministry of Defence, instituted the Military History Archives and the Military History Museum. Work began almost immediately in the rooms of the barely finished building of the Hungarian National Archives, since apart from the Great War material, there could not be any delay with the systematic collection of the relics and documentaries from the two major political transformations, the Hungarian (People’s) Republic, and the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic (formed on 21 May).

The fate of the Royal Hungarian Military History Archives (“Military Archives”) and the Royal Hungarian Military History Museum (“Military Museum”) was therefore linked together from the very beginning. Their names occasionally changed during the following decades, reflecting on the current situation, in which the two public collections existed with separate headquarters and organizationally sometimes separated, sometimes joined until 1945. Usually it was part of the Royal Hungarian Defence Forces’ organization, but was attached to the Ministry of Culture for short periods.

The Military History Museum that safeguarded a collection of nearly 5,400 artefacts was housed in a dedicated part of the Maria Theresa Barracks in June 1920. This site was not capable of accommodating large size pieces, such as cannon or vehicles. Under the harsh economic circumstances all that could be achieved was the modest preservation of the assembled artefacts. The physical opportunities for the acquisition of new items decreased to the minimum, while artefacts were delivered continuously from disbanded military units. Insufficient space did not allow any public exhibition. That notwithstanding, under these constrained circumstances the organizational and operational protocols of a new national public collection were created and personnel recruited. A warehouse was opened on Gubacsi Road to store large size military technical objects.

A part of the Maria Theresa Barracks on Üllői Road was allocated to the Military History Museum in 1921. It accommodated storages, offices and exhibitions until 1928

The bi-functional institution was divided in November 1922 and the Museum became an independent institution under the command of Chief Councillor, Rear Admiral Károly Lucich (1868–1952).

In organizing the Museum and making it prosper, Kamil Aggházy earned everlasting merit and his life – especially after being crippled on the battlefield – as a self-educated military historian, scientific and institution organiser intertwined inseparably with the fate of this public collection. He chose his colleagues quite fortunately: the versatile cultural historian, Béla Borsody-Bevilaqua (1885–1962), the numismatist Rezső Karny (1876–1958) or Aladár Görgey (1883–1945), head of the library, who had been saving and identifying the artefacts until his death in the autumn of 1945.

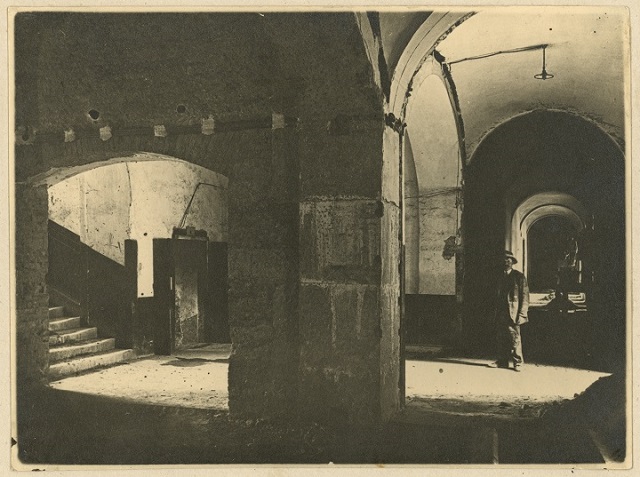

Exhibition hall No. IV at the Maria Theresa Barracks

The Nándor Barracks became the final home of the Military History Museum. It was rebuilt between 1926 and 1929 to comply with museum requirements

The Military Museum started moving from the Maria Theresa Barracks to the Nándor Barracks in 1928. The unloading of works of art at the entrance from Tóth Árpád Promenade, 3 June 1929

Having been reconstructed between 1926 and 1929, the annexe of the Nándor Barracks in the Castle of Buda facing the Vérmező was chosen to be the new home of the Museum. It was not until 1937 that the former barracks, which provided modern and suitable accommodation, had the collection installed and the permanent exhibition ready. On May 29 of the same year (on Heroes’ Day) the first exhibition, in thirty-six exhibition rooms and on the corridors that had a total length of 260 metres, was opened to the public. Visitors could view the history of the period between 1686 and 1914 on the ground floor of the building, while the 1st floor hosted the memorabilia of the Great War, and the 2nd floor provided space for the specialised collections. Regent Miklós Horthy honoured the opening gala with his presence. Minister of Defence Vilmos Rőder gave an inauguration speech.

The Military History Museum is bordered by Tóth Árpád Promenade (previously Bástya Promenade) from the western castle wall. The picture was taken in the 1930s, when a slope connected the Museum with Lovas Road below

Tóth Árpád Promenade and the Esztergom Bastion with the artefacts of the Museum and recently planted trees in the 1930s

The completed permanent exhibition with a floor area of 3600 square metres was opened by Minister of Defence, Colonel General Vilmos Rőder on 27 May 1937 as part of a high-profile ceremony

Nothing can better evidence the incremental significance of the Museum than the acquisition of relevant and high-value national treasures in the 1920s and 1930s. The return of more than 2,000 artefacts relative to Hungary back to their land of origin from the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum in Vienna had been considered a milestone. The acceptance of these items, pursuant to Article 177 of the Treaty of Trianon, took place in an orderly fashion at Baden bei Wien on 26 May 1926 in full conformity with the accord entered into with the Austrian federal government. At the same time, due to generous donations by private individuals and other bodies, by further deposits, acquisitions and domestic and foreign auctions, the collection was enriched with many remarkable artefacts and objects such as national relics dating to the 1848–1849 War of Independence, the military uniforms of members of the Habsburg family, memorabilia collected from military units, and complete collections. The Museum established its national collection network and liaison with other domestic and foreign associate institutions in those years.

A series of Hungarian military celebrations at the Castle of Buda was initiated by the Museum in 1920. The Museum took on the lion’s share of the organization of the so-called Commemoration Day of Mohács (in 1926) as well as the installation of the commemoration plaques along the route between Budapest and Mohács. It also earned impressive accolades in the completion of the survey locating Hungarian war graves and in caring for the graves of eminent soldiers that rested in peace in various cemeteries. The institution established a rural correspondence network and an acquisition team with 140 personnel. It founded the Hungarian Military Museum Society in 1924, which published a journal titled Hadimúzeumi Lapok (“Military Museum Journal”), later História (History), which published both specialist and general articles, as well as news about the Museum and for veterans, it also organised affiliate societies in the country (in Debrecen, Nyíregyháza, Szeged, etc.), and it lined up veterans associations to serve the Museum with their activities.

The relationship between the Military Museum and the Hungarian National Museum has a peculiar history. Following the Museum’s move to the Castle District, the Minister of Defence ordered the revision of the Institution’s and its collections’ activity of the past ten years. The ambits conducted with the inclusion of specialists from the National Museum also provided an opportunity to divide the overlapping coverage of the collections of the two institutions in October 1935; as regards the purviews of their respective collection of military historical memorabilia, the year of 1715 was determined as the dividing point, because this was the year when the Hungarian Diet ratified the setting up of a standing army. Following upon the accord reached between the museums artefacts were exchanged. The Military Museum handed over artefacts and objects dating to the Ottoman occupation of Hungary and the National Museum delivered the priceless relics of the 1848–1849 War of Independence.

Hall No. I just before the opening, 1937

The building of the Military History Museum, the courtyard of the former Nádor Barrack, around 1940

The library of specialised books (library of manuals, today called the Book Collection) has always been connected to the Military Museum since its foundation. Its collection of military regulations is unique in Europe. A studio for painting and statuary, another one for arts and crafts, as well as a locksmith’s and joiner’s workshop have also been part of the Museum from the beginning.

During the Second World War, 1943 was the last year when the Museum functioned with full capacity. All of the exhibitions could be visited in the summer of that year, what is more, new features, such as the so-called Russian Hall, opened. One of the officers employed at the Museum was assigned to enter military operation zones to carry out active collecting of artefacts. Frequent air raids however forced the personnel to bring into effect the regulations for the protection of the artefacts. The valuable artefacts were packed in the beginning of 1944 and were placed in containers in the cellar of the Museum until the summer of the same year. Exhibitions in seven rooms could still be visited though.

After the frontline reached Hungarian territory, the Minister of Defence ordained the relocation of the Museum personnel and the collections in October 1944 in order to protect the high priority national stockpile. The assortment to be rescued was delivered to the Erdődy Manor in Somlóvár that was connected to the village of Doba in Veszprém County. Although the removal order unambiguously concerned valuable objects, it is impossible to ascertain what exactly was transported. On the strength of the available roster, 883 containers were carried by ten railway freight cars. To date, no records have been found which shed light on what became of the evacuated items. At Somlóvár, the relocated personnel could not conduct any professional activity, but Géza Turányi (Thurner) (1892–1952), a tireless secretary of the Museum used his personal connections fully to prevent the collection under his care to be destroyed or transported abroad. In 1945, the manor house was utterly abandoned as Soviet troops approached; later the Museum personnel were captured by the Soviets and the items stored there were left unguarded. Up to 80% of them were destroyed. Later, the Soviet supreme command had a part of them, including the flag collection, transported to the Soviet Union.

In 1945, serial bombing and fighting in Budapest, especially in the Castle District inflicted severe damage on the building of the Museum. Its south-western corner was reduced to rubble, and three-quarters of its roof structure collapsed. Its surviving sections became useless and the debris covered almost everything that had not been evacuated. Books pierced by bullets, water stained and muddy scripts, as well as fragments of decorations and medals vividly demonstrate this event, even today. The vast majority of the exhibition showcases was destroyed, and all of the windows were smashed.

The Military History Museum’s building was seriously damaged due to the bombardments and the Siege of Buda Castle in the Second World War. The Görgei statue was destroyed